UNHCR Policies in Egypt In light of global crises

Background to understand the situation

- (Refugees in Egypt – Nationalities and numbers of refugees in Egypt in 2022)

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- UNHCR’s Missions in Egypt

What UNHCR is doing for refugees in Egypt

- Refugee Status Determination

- Registration (risks of arrest and forcible deportation in case of delay in registration – the principle of non-response in international law and the commitment contained in the Egyptian Constitution)

- Livelihood Aid

- Protection services (reports accuse Egypt of failing to protect refugee women)

- Documented cases that support alleged violations in international reports:

Supporting the refugee to reach a durable solution (the fate of the refugee situation)

- Voluntary return

- Local integration

- Resettlement to a third country

ResultsandRecommendations

Methodology

The research mainly targets public opinion in Egypt, international and civil organizations, especially the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, those interested in migration and asylum affairs, aid and grant providers, as well as government decision-makers and legislators, in order to provide the best available assistance to refugees residing in Egypt, and take into account the conditions and situations in which they live, and urge those targeted by the study to work in accordance with international conventions and play their role in developing services and integration programs, searching for sources of funding and directing assistance to those who deserve it by studying cases in a more professional manner

Several research methods were adopted to collect data, namely:

- Survey with Migrant Community Leaders: This survey aimed to assess migrants’ access to basic services in Egypt, and was conducted from January 2022 to September 2022, where data was collected through personal and telephone interviews with 48 leaders of migrant communities of different nationalities including Syria, South Sudan, Sudan, Ethiopia, Guinea, Libya, Comoros, Eritrea, Somalia, Yemen, and China. The survey included questions about each nationality and information about the characteristics of migrants such as age, gender, location, marital status, and the level of education.

- Since the beginning of the crisis, especially with the beginning of the (Covid-19) pandemic, the Refugees and Migrants Program at the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF) has sought to clarify the reasons for this decline in services through some workers with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), whose identities were concealed by the program in view of the UN policy of speaking to the media.

- Desk review, research, previous reports, official statements, and daily monitoring of protection and legal support officials and case management at ECRF, where it received several complaints from various nationalities from registered refugees and asylum seekers related to the scarcity of assistance in the face of living, health and children’s education, and the need for psychological, legal or material support.

Introduction

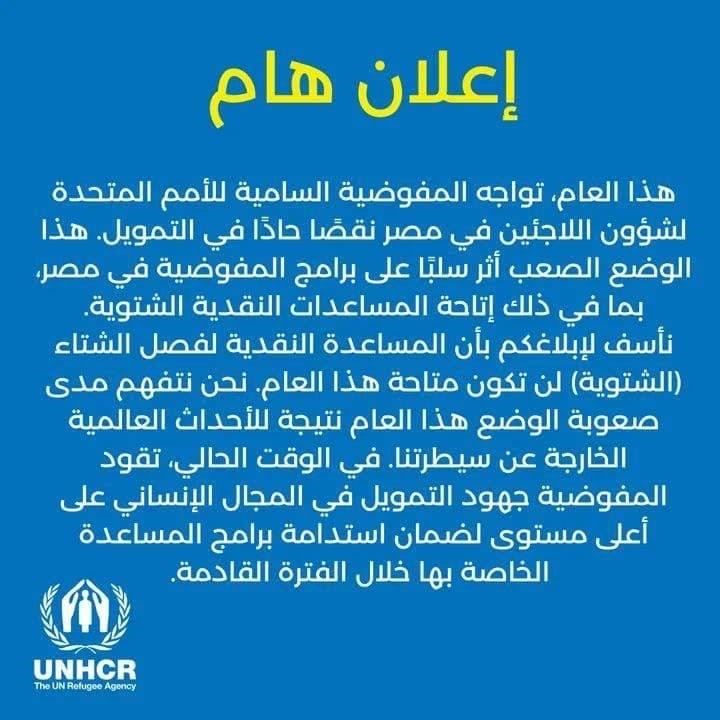

At the beginning of November, the United Nations High Commissioner announced through its websites the cessation of winter assistance[1], and justified this for reasons due to the extreme lack of funding resulting from external global events. At the time of this announcement of suspension of aid, hundreds of thousands of refugees were already in bad condition due to the suffering they had not yet recovered from due to the Corona pandemic and the closure that occurred after it. The most important impact of the pandemic was in shifting the economic paths of international attention. and development in other directions, driven by the political tensions that the world has witnessed recently.

If this was the case with registered refugees who should have been enjoying the protection umbrella, how about those who are still waiting for registration and are not provided with any assistance in the first place? The current situation leads us to ask other important questions after 10 years of the most recent refugee influx to Egypt that followed the events of the Arab Spring in 2011; questions related to how the refugee status is being determined? Who is excluded from the registration and protection despite their requests? Is the reason for the decline in support because of the High Commissioner’s preoccupation with the crisis of Ukrainian refugees and before them Afghans? Or does the influence of donor countries affect UNHCR’s policies, the preference of some nationalities and the neglect of others?

Whatever the reasons, is the Organization doing what it must according to its current capabilities? What does UNHCR offer African asylum seekers trapped for years in Egypt? Does it intervene to protect minorities such as Uighurs and oppressed people of different nationalities? Does it implicitly urge Syrians to voluntarily return by reducing subsidies? And is this related to the policies to reduce migration across the Mediterranean and the policies of voluntary return of Syrians, which began with the return of Syrians from Lebanese camps? The report attempts to explore the lives of refugees in Egypt to try to answer these questions. [2]

Background to understand the situation

According to the 1951 Convention on Refugees, which is among the international conventions and treaties signed and ratified by Egypt, international law classified refugee situations into: flight of people and their search for refuge due to civil wars and armed conflicts, fear of persecution because of race, sex, religion or opinion, flagrant violations of human rights, occupation or external aggression, poverty, famine, disease, natural disasters, as well as cases of loss of nationality.

Among the most important rights stipulated is the granting of identity papers and travel documents to all refugees, as well as the treatment of refugees in the same way as state citizens in terms of freedom to practice religion, religious education, access to justice, access to legal aid, access to primary education, relief and assistance, and other rights.

Refugees in Egypt

Egypt is not new to refugees heading to it, settling in it, and integrating in its society in many cases. During the twentieth century, Armenians resorted to Egypt to escape the massacres of the Ottomans in 1915, refugees of European nationalities fleeing the hell of World War II, and Palestinians refugees after the 1948 war. Egypt also received large numbers of refugees from Sudan following the civil war in 1985, as well as Somali families after the civil war in Somalia in 1991; in addition, Iraqis, after the US invasion came as refugees to Egypt, and finally the people of the Arab Spring countries sought refuge from Syria, Libya and Yemen since 2011 and the events that followed.

Nationalities and number of refugees in Egypt in 2022

At present, Egypt hosts many refugees and asylum seekers. According to the Egyptian government, the country hosts about 6 million migrants, and while other parties, the most important of which is the International Organization for Migration of the United Nations, believe that this estimate has increased recently and confirms that currently the number of migrants in Egypt is estimated at about 9 million migrants[3]. According to the latest statistics of the organization issued in August 2022[4], the order of the number of migrants was as follows:

Sudan: 4,000,000

Syria: 1,500,000

Yemen: 1,000,000

Libya: 1,000,000

Saudi Arabia: 600,000

South Sudan: 300,000

Somalia: 200,000

Iraq: 150,000

Palestine: 135,932

Ethiopia: 17,000

Other nationalities (132 nationalities): 109,650

Total: 9,012,582

According to the latest statistics of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), issued in January 2022, there are 273,152 refugees registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) of 65 different nationalities, 50% of whom are Syrians[5]. The number of refugees and asylum seekers registered from different countries in Egypt is as follows: Syria 137,599, Sudan 52,446, South Sudan 20,970,Eritrea 21.105, Ethiopia 15.585, other nationalities (from 60 countries) 25.447.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

UNHCR is the only international organization with a mandate to protect refugees at the global level since the 1951 Convention. According to its mandate the responsibilities of the High Commissioner mainly concern several groups of persons who are the subject of attention of UNHCR; these are: refugees, asylum seekers, returnees to their countries, and stateless persons, and provides specific services to these people through programs, and in partnership with many governmental and civil agencies and international organizations.

UNHCR’s Missions in Egypt[6]

UNHCR’s mandate in Egypt is to provide the following main services: refugee status determination, registration, implementation of durable solutions for refugee status (voluntary return), protection services of all kinds, livelihood and earning development programmes, education, health, and cash assistance.

What is UNHCR doing for refugees in Egypt

- Refugee Status Determination

Refugee Status Determination (RSD) is the legal or administrative process by which governments or UNHCR determine whether a person seeking access to international protection is considered a refugee under international, regional or national law.

- Registration

International protection for asylum-seekers and refugees begins with admission to the country of asylum and registration and documentation by UNHCR. Registration and identification of refugees is essential for the persons concerned as well as for countries to know the number of arrivals and facilitate access to assistance and protection. This allows UNHCR to identify people with protection risks or special needs and those in need of assistance. Registration helps protect refugees from refoulement, arbitrary arrest and detention.

Rights of UNHCR-registered refugees

In Egypt, the Egyptian government delegated the registration process to UNHCR based on the memorandum of understanding signed in 1954. The registration process has evolved by modern means such as iris and fingerprint scanning. In addition to facilitating access to services, registration allows refugees and asylum seekers to organize their stay in Egypt.Once registered, they can obtain a renewable residence permit which gives them freedom of movement around the country.

- Why would a migrant not receive UNHCR protection? Who is excluded from registration and placement despite applying for it?

Sources in the organization say that those who are denied registration are often from the groups that participated in war crimes, genocide, torture, or sabotage, or those with suspicious or criminal records or those who have previously been convicted of some crimes.

Registration therefore legitimizes the refugee’s existence, residency and services, and protection against forced deportation.

Risks of detention and forced deportation due to UNHCR’s delay in registering refugees

From the date of the first interview conducted by the asylum seeker until the adjudication of his application, time passes that may reach years in some documented cases. With the beginning of the Corona pandemic, UNHCR offices reduced their work and followed the policy of remote work, conducting interviews and receiving applications electronically, and the number of employees and those working in receiving cases decreased. Refugees no longer had anything but the announced e-mail to communicate, which increased the suffering of applicants and prolonged their waiting periods.

- Are there potential risks that a refugee may face during and because of the waiting period, such as arrest, threat of deportation, or inability to carry out formal or necessary procedures?

70% of those surveyed responded that there are such risks and that some of them have already been exposed to them, the following are some of those risks:

Risks of Arrest:

According to testimonies of refugees, failure to register exposes them to the risk of detention by Egyptian security and the threat of deportation in the absence of a valid residency. One of the refugees says: “In the event of any general problem or personal problem between you and another person, you can be deported, so we avoid official transactions, and we cannot file a complaint or write a warrant with the police, or resort to litigation.”

UNHCR sources explain regarding cases of detained migrants and asylum-seekers that registration was done at some time inside places of detention when the organization knew of the presence of refugees detained somewhere, but this possibility has stopped, because the authorities refrained from allowing UNHCR to register inside places of detention. The source adds that even when there are several detainees in places of detention, all UNHCR can do is send an official letter from the organization demanding the release of detainees and a commitment not to deport them and enable them to receive UNHCR protection. According to the source, even these letters are ignored and not answered by official authorities or security authorities.

Risk of forced deportation

The seriousness of forcible deportation and its definition according to the United Nations:

Article VIII of the Statute of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) provides for solutions to the refugee problem, stating: “The task of international protection includes preventing the forcible return of refugees, assisting the stability of asylum-seekers through procedures that are not complicated, providing them with legal aid and advice, making arrangements that guarantee their safety and security, encouraging safe voluntary returns, and assisting in their resettlement.”[7]

There is also the principle of non-response in international law and the obligation contained in the Egyptian Constitution, which stipulates in Article 91 that: “The State may grant political asylum to any foreigner persecuted for defending the interests of peoples, human rights, peace or justice. The extradition of political refugees is prohibited, all in accordance with the law.” Article 93 of the Egyptian Constitutionstates that: “The State shall abide by international human rights conventions, covenants and covenants ratified by Egypt, and shall have the force of law after their publication in accordance with the prescribed conditions.”

In violation of these obligations, ECRF has often monitored cases that were forcibly deported to conflict areas during the years 2019, 2020 and 2021, most of them Somalis and Eritreans, who were deported by Egyptian authorities without paying attention to the statements issued by ECRF and other human rights bodies that condemned these actions and their danger to the lives of refugees and their contradiction with the rules of humanity and international conventions. No announced action appeared by the United Nations High Commissioner regarding those who were deported, and most of them had spent time in separate places of detention in Salloum, the Red Sea or Aswan in southern Egypt. UNHCR knew or was informed of their whereabouts and the date of their detention.

Recently, UNHCR has been alerted to the dangers of deporting refugees and speeding up the registration of refugees from the Uyghur minority, after many cases have been arrested and deported in violation of international law and the constitution, including many cases that contacted ECRF requesting protection from the threat of deportation, and mediation with the United Nations High Commissioner to expedite registration. However, so far, the matter is still selective, and the UN Commission is still unable to reach a commitment on the part of the Egyptian state when it comes to detention or deportation decisions.

Risk of discontinuation of essential services:

There are also a number of services that the immigrant would receive upon registration with the United Nations High Commissioner and obtaining legal residency. Those services are denied in cases of nonregistration, including non-acceptance in work and the fear of the refugee from raiding the workplace, the inability to study and the difficulty of registering children in school, suspension of communication lines unless the residence is renewed, and this makes communication with UNHCR in that period impossible and the refugee may lose financial aid or an interview appointment.

These reasons make some refugees prefer to carry a passport instead of registering with the United Nations High Commission. Some of them may have to travel to see their families, some of them are on the move and need to show the passport in government facilities such as the post, or to obtain official documents such as a driving license, university certificates, travel and other reasons such as the search for a better living condition and the possibility of obtaining an annual residence that enables them to go out and return and visit other countries to search for a job opportunity, pilgrimage and owning a mobile line and opening a bank account. However, it is not easy for some nationalities to carry a passport because of the fear of entering their country’s embassy for security reasons or because of the exorbitant fees such as is the case with Syrians, which the issuance of a passport amounts to 1200 pounds.

Also, most of those surveyed stated when asked about the existence of guidance or support on completing procedures in government places that there was no such assistance, and more than half of those surveyed decided that the treatment of passport employees when obtaining or renewing residence permits ranged between bad to acceptable.

- Livelihood Aid

Cash assistance[8]

Before the announcement we referred to in the introduction about the cessation of financial aid last month, UNHCR considered refugees and asylum seekers in Egypt among the neediest urban poor, as they have limited livelihood opportunities and many of them struggle to meet their needs. Therefore, UNHCR believes that providing refugees with sufficient cash to enable them to meet their needs is necessary, and it was providing monthly multi-purpose cash grants to a specific percentage of refugees in Egypt through Egyptian post offices to cover the expenses of their basic living requirements.

All refugee and asylum-seeker files registered with UNHCR were evaluated to identify the most financially vulnerable people to select high-risk files. Refugees were conducting an evaluation interview with UNHCR’s partner Caritas for basic needs, and despite the small size of this percentage that was eligible for aid compared to the number of refugees, many families were dependent on it, especially since the entire refugee community suffers from permanent financial dilemmas, the most important of which are the accumulated rent of housing, the lack of job opportunities, and the absence or illness of the family breadwinner or his arrest or illness in addition to care, nutrition and education requirements of children.

This suspension of help comes at this time to increase the suffering of refugees. While UNHCR has admitted in its announcement of the cessation of aid due to the severe lack of funding, it did not explain the reasons for the lack of funding, and whether Syrian refugees have joined their predecessors of African refugees forgotten for decades without support or intervention? Or whether the Syrian crisis is no longer an emergency crisis, and what draws global attention now are other crises, such as the influx of Afghan refugees after the withdrawal of coalition forces or the Russian-Ukrainian war crisis. UNHCR has not clarified how it will overcome this shortfall and how it will raise the grants and funding needed to meet its commitments.

Education Grants & Services

UNHCR calls for the registration of refugees and asylum seekers in public schools, and the Egyptian government has allowed citizens of Syria, Sudan, South Sudan and Yemen to access the public educational system in Egypt on an equal basis with Egyptians. However, this is not enough when children suffer coping problems, especially with the poor state of formal education, as well as the language barrier for some nationalities and the spread of violence and bullying and forcing many families to rely on children as breadwinners for the family or a source of income for it.

UNHCR offers a number of scholarships through CRS, but their conditions are not easily fulfilled for everyone and they are not sufficient in terms of the large number of refugees.

Livelihoods and economic integration

UNHCR aims with this program to help refugees and asylum-seekers support themselves and their families by providing them with training and helping them find a market for their skills and goods, but this is done through its partners for a very small number compared to the number of refugees who need it, and the program does not guarantee continuity, which makes it a cosmetic goal that does not actually contribute to alleviating the refugee crisis. More than 65 percent of those surveyed decided that no one had contacted them about these projects and they did not know of their existence. Some replied that these initiatives are offered to certain people who frequent organizations on a regular basis.

Healthcare

In 2016, the Ministry of Health and Population and UNHCR signed two memoranda of understanding granting refugees and asylum seekers of all nationalities equal access to primary, secondary and emergency health care as Egyptian citizens[9] but these primary services such as medical examination and maternal and neonatal care in family medicine units do not meet the most important medical needs such as treatment of chronic diseases, necessary emergency operations, prosthetic devices, the costs of medicines and support for disabilities, all of which are left to refugees to face alone without assistance.

- Protection Services

Those address important aspects such as protecting children from abuse and violations, providing support for sexual and gender-based violence cases such as legal, psychological and advocacy support, psychosocial services, as well as support and legal assistance to refugees.

These programs still serve a small number of cases compared to the number of refugees, and their continuation is also linked to the continued flow of grants and funding. According to the survey of cases on which this report relied, 60% of the refugees who participated in the questionnaire decided that they did not receive any of these services, while 30% decided that they did not know of the existence of these services and how to access them, while 10% decided that they received some of these services.

Legal Aid

St. Andrews Refugee Services Stars (StARS) provides information, consultations, referral, representation and advocacy to asylum seekers and refugees in Egypt free of charge in partnership with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and it is one of the forms of assistance that refugees always need, whether because they are not familiar with the procedures and laws or because they come into legal difficulties or lose official papers and need issuance of papers and documents for them and their families. Half of those surveyed explained that they were in need of legal support at some point.

However, these services, which UNHCR announces to be provided free of charge, are not enough for the number of refugees, and they always complain about their negligence and ineffectiveness, especially when it comes to detention or litigation cases that need perseverance and urgent intervention, such as supporting women who have been subjected to violence and harassment. There are reports that have been issued recently accusing Egypt of failing to protect refugee women from sexual violence[10]. The report says that a number of victims were unable to report incidents for fear of being arrested because of the end of the legal period of their stay, while others did not refer their cases to forensic medicine, and were unable to receive medical care. The report issued by Human Rights Watch last month explained that the police asked the victims to provide the full names of the defendants to agree to write a report of the incident, which the victims could not know, nor could they afford to hire lawyers. [11]

It is clear from these reports the failure and complicity of the police to support refugee victims for reasons related to societal perception and discrimination against refugee women, which is something that ECRF has monitored a lot through its documented cases related to harassment and rape attempts and what follows in the event that the victim goes to complain to the authorities without assistance. ECRF has documented cases that have been subjected to serious and varied legal and procedural violations such as enforced disappearance, detention without charges, trial or known location for different periods, rape and harassment. Some of them were assaulted and accused of engaging in prostitution, and the victims were not referred to the medical authority to prove their statements or charge the aggressors:

Documented cases that support alleged violations in international reports:

The right to justice and the right to litigation before the national judicial system is guaranteed to refugees in the host country in accordance with the Egyptian Constitution, which stipulates in Article 151 that:

“The President of the Republic shall represent the State in its foreign relations, conclude treaties, ratify them after the approval of the Chamber of Deputies, and shall have the force of law after their publication in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution…”

Accordingly, the national judge, in his commitment to the application of the constitutional text, is obliged to apply the international conventions on the status and rights of refugees, to which Egypt acceded by the decision of the President of the Arab Republic of Egypt No.331 of 1980 on the approval of the United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees signed in Geneva on 28/7/1951, published in Official Gazette of November 26, 1981, No. 48, which stipulates in its clauses that:

Article 16: Right to litigation before the courts

- Every refugee shall have, on the territory of all the Contracting States, the right to litigate freely before the courts.

2- Every refugee shall enjoy, in the Contracting State in his habitual residence, the same treatment as a national enjoys with regard to the right to litigate before the courts, including legal assistance.

Article 35: Cooperation of national authorities with the United Nations

However, it seems realistic through the cases documented by the ECRF over the last year, 2022, within the framework of its program to provide legal support and advocacy to migrants, and through the documented testimonies of these cases, that the accounts that talk about violations of the legal rights of refugees contained in international reports are characterized by a lot of credibility. The following are but a few examples out of a large number of cases:

- Chadian refugee forcibly disappeared in December 2021

The 66-year-old Chadian refugee (T.A.) registered with the United Nations High Commissioner in Egypt, has been living in Ard El Lewa in Cairo since his arrival in Egypt on November 20, 2014> he was a renowned political figure in Chad, and was an opponent of the Chadian government, left the country for exile in the United States, then in 2014 left the United States and sought asylum in Egypt, where he has been living ever since. He always communicated with his family via email, letters, phone or through his close friends to let them know that he was safe and healthy.

At present contact between him and his family has been cut off. They consider him missing since September 2020. His family, friends and acquaintances visited all the major hospitals, inquiring with the local authorities, and even visiting the morgue to no avail. They communicated with UNHCR and Amnesty International, but did not receive any news.

- Syrian refugee forcibly disappeared in November 2022

Syrian refugee (A.F.) aged 35 years has been living in Egypt since 10 years and registered with the United Nations High Commissioner. Last October he was arrested on the street while going to work, and then a group of five security men in civilian clothes and a person in police uniform went to the house and searched it. After twenty days his family received a short call from him asking them to hand over his passport, papers and some clothes to a member of the police department in the city where he lives. His father did not know his condition or location and has not received any other communication from him so far.

The documented testimony contains evidence of the confiscation of funds that were in the possession of the refugee and others from his home, documents and papers, and the family hired a private lawyer and sent reports to the Public Prosecutor and the Ministry of Interior about the arrest and disappearance.

- Enforced disappearance and arbitrary detention of Yemeni refugee, followed by charges related to freedom of belief

The Yemeni refugee (A. S. A.) has been living in Egypt for 7 years. He applied for asylum and registered with the United Nations High Commissioner, after repeated attacks against him and his family in his country of origin because of his religious belief, the latest of which was setting fire to his house, causing the death of his wife and injury of one of his sons, which prompted him to flee to Egypt, where he married, had children and communicated with his family.

In December 2021, security in plainclothes and police uniforms stormed his house, where they searched the house and did not show any legal warrant for arrest, as well as did not tell him the reason for his arrest nor enabled him to contact his lawyer. They searched the house and seized 4 laptops, as well as a number of documents, his UNHCR card and his ID card.

After that, the victim was subjected to a period of enforced disappearance. His wife and children searched in all police departments without finding him throughout the period from the date of arrest on 15-12-2021 until 30-12-2021 until a person called the refugee’s son and informed him that he was detained with his father in a secret prison. Thus, the family knew where he was detained and the wife was able to visit him and said that he was in a bad psychological and physical condition, especially since he was unable to take his medications and was interrogated for many hours and was not allowed to see what he was made to sign. He was initially accused of charges related to religious belief and proselytizing, then contempt of religions and joining an illegal group. A misdemeanor of Emergency Supreme State Security was filed against him, and his detention continues to be periodically renewed.

- Sexual assault and rape of Sudanese refugee

(F. A.) is a female Sudanese refugee who entered Egypt in May 2015 seeking asylum. She has four children from two marriages where the latter husband was constantly abusing her and the children, as well as sexually harassing her eldest daughter. She said that her eldest daughter had previously been sexually harassed by Sudanese men when she was 8 years old, and when asked why she neglected the accidents that her daughter was exposed to more than once, she said that no one would help her and that she had gone to the police more than once but they would refuse to help her or file a report.

She continues: the violence increased from the husband, I was severely beaten and threatened with death; he hung a rope from the ceiling of the room, threatening to hang me, and said that the Egyptian police would consider it a suicide and would not pay attention to her because she was a Sudanese refugee.

In 2019 she was raped by a group of Sudanese men while she was cleaning houses and without the intervention of any party to help her, which resulted in her pregnancy and she gave birth to the fourth child, whose father she does not know and was registered at birth in her husband’s name.

Six months ago, the husband disappeared and the wife did not know his whereabouts. He had left the rented apartment, so she left it as well, and she currently lives with the four children with an acquaintance.

Her husband had applied for registration with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in 2015 and his application was rejected in 2019, so the wife and children are without papers or registration with UNHCR.

The mother and children were all in need of urgent psychological support, legal assistance, child protection and registration of the youngest child, and also requested assistance in enrolling children in schools since all of them dropped out of education.

- The murder of a Sudanese child, a case that included illegal gathering

The events began in October 2020 in Cairo when the Sudanese child (M.H.) 12 years old was stabbed to death by an Egyptian person who was in disagreement with the child’s father; the accused was arrested and appeared before the investigation authorities and the Public Prosecution began investigating the accused without delay and the killer confessed to his crime before the Public Prosecution, which decided to imprison him

However, the crime sparked great anger among the Sudanese in Egypt, who gathered console the family of the dead child, upon which they were detained in large numbers and charged with demonstration, gathering and vandalism. The Egyptian Public Prosecution issued a statement to clarify the details of the incident and its motives and a statement of the arrest of the accused and investigation with him and announced taking the necessary legal action against the accused

After a while, Egyptian security authorities released a number of those arrested and kept others who were charged on cases. All of them were holding asylum cards issued by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, according to the seizure report; still, security forces confiscated their mobile phones and documents, and this incident left great effects on the Sudanese community.

The incident also resulted in the Sudanese complaining that UNHCR’s legal support was unable to take into account their interests; they also complained about the failure of UNHCR’s partner, St Andrew, to provide protection services after the incident.

- Enforced disappearance and torture of Syrian refugee for religious belief

(J.A.) is a 33-year-old Syrian refugee who has been living in Egypt for 10 years. The refugee was harassed at his workplace by a police officer who used to ask for services free of charge, because he knew that the refugee follows a non-religious social ideology and continued to persecute and harm him by blackmailing him and threatening to inform the surrounding families that he was not religious. He put the refugee under constant surveillance. As a result of the persecution and transgression of the police officer the refugee was arrested on 12-07-2021 and remained detained for 18 days, and was then released in poor condition and almost unconscious.

According to what has been documented, the refugee was subjected to several forms of violations such as being detained with criminal prisoners, and inciting prisoners against him because of his religious belief in order to physically harm him and insult his dignity. He was exposed several times to fainting and losing consciousness due to being beaten, tortured and burned with cigarettes in his body by police sergeants.

As a result, he was admitted to hospital in an unstable condition with bruises, festering wounds, a broken rib and a swollen jaw as shown in the photos and medical reports submitted by the witness.

- Sexual harassment and killing of Sudanese refugees

(H.A.) is a young female Sudanese refugee living in Cairo. An Egyptian resident of the street followed the victim as soon as she entered the elevator of the property, sexually harassed her and tried to rape her. She resisted him, which caused her injuries in the form of bruises and scratches in various parts of her body, and she sought help from the neighbors until she was able to escape and go up to her family’s apartment.

The brothers went down to confront the assailant, who was accompanied by his friends, who assaulted the two brothers, which led to the injury of one and the death of the other.

The victim took her two injured brothers to a hospital, but they refused to receive them, and the two brothers continued to bleed from their wounds until she took them to Kasr Al-Ainy Hospital and they were left at the reception bleeding until their identification papers were brought.

The victim explained that the entire incident is documented by cameras as well as the incident of harassment. The second defendant fled after seizing some cameras on the street, and according to the victim, the police know his whereabouts and have not taken action to arrest him so far.

She also documented her exposure to ill-treatment, questioning and intimidation in her statements. The police also committed illegal procedural violations such as delay in writing the report and not transferring her to forensic medicine immediately after her reporting the assault. The victim said that police officers accused her of having consensual sex with the defendants. The family needed legal support but did not have enough money to follow the procedures.

All those refugee women who are victims of harassment, rape and abuse, forcibly disappeared, and detained for reasons related to freedom of opinion and belief need legal and psychological support as well, but the support that UNHCR says it is providing does not reach them.

Durable solutions (voluntary return and resettlement programs in a third country)

The fate of the refugee status

Through the conventions, countries have tried to develop a vision to solve the refugee problem through:

Voluntary Return:

It is the possibility of refugees returning to their homes in their countries of origin when their lives and freedom are no longer threatened. Voluntary repatriation is usually seen as the best long-term solution by the refugees themselves as well as by the international community, so UNHCR’s work to find durable solutions to refugee problems is geared towards enabling refugees to exercise the right to return to their country in safety and dignity.

UNHCR in Egypt is working to facilitate voluntary return to certain areas[12] of Sudan and Somalia, and for Ethiopians to Addis Ababa, and conducts surveys of intentions with Syrian refugees to measure their interest in return, and prepares for the possible return of Syrian refugees in the future, but the international community still considers that the situation in most places in Syria remain unsafe to achieve the conditions for voluntary return as defined by international law, which is to be a voluntary, safe and dignified return.

In September 2021, Amnesty International published a report entitled “You are going to your death”[13] documenting grave violations practiced by the Syrian regime’s security men against refugees (men, women and children), who returned to different areas in Syria. The documented cases included different areas in Syria, including Damascus and its surroundings, and that violations against returning refugees occurred while entering Syria at border points and days after entering security centers, and therefore Syria is not a safe country for the return of refugees because the principles required by the United Nations for voluntary return are not fulfilled, which are that the return be safe as well as with dignity.

Amnesty International also explained in its annual report[14] on the human rights situation in Syria for 2022, specifically with regard to the rights of refugees and internally displaced persons:

“By the end of the year, the number of internally displaced people in Syria since 2011 had reached 7.6 million, while 6.5 million had sought refuge elsewhere outside the country, and the deteriorating humanitarian situation in neighboring countries had created administrative and financial obstacles in obtaining or renewing residency permits, so a number of refugees continued to be forced to return to Syria, with some subjected to arrest, torture and other ill-treatment and enforced disappearance.”

“Refugees, including children who returned to Syria between mid-2017 and April 2021, have been subjected to arbitrary detention, torture and sexual violence, as well as enforced disappearance by government forces, and five refugees have died in custody who had previously been subjected to enforced disappearance,” Amnesty International’s report adds.

Cases of nationalities from the Horn of Africa have also been documented, confirming that they prefer to migrate across the sea rather than risk voluntary return, especially young people and adolescents who are drawn into the ongoing armed conflicts between Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia.

Local integration:

It is when the host country allows refugees to integrate into the country of first asylum, does UNHCR provide adequate programs to achieve integration policies with the host community? The answers shown by the questionnaire were 50% negative and 40% ‘I don’t know’. In fact there are some nationalities who feel very integrated for well-known reasons, such as Syrians, whose answers to the question: “What percentage do you feel integrated into Egyptian society”? were as follows:

“Excellently, to a great degree integrated, 99%, to a great extent 90%, much integrated 80%.”

The majority of African refugees answered the same question:

“There is no sense of integration 5%, 5%, 1%, no sense of integration, pure non-integration, not at all, no sense of integration”

Resettlement to a third country[15]:

For refugees who cannot return either due to ongoing conflict, wars or persecution, resettlement in another country is an alternative option, as resettlement involves selecting and transferring refugees from a country where they have sought protection to a third country that has agreed to accept them as refugees and will grant them permanent resident status.

This provides the resettled refugee as well as his or her family or dependents with access to civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights similar to those enjoyed by citizens, and with it the chance that the refugee will eventually become a naturalized citizen in the country of resettlement.

Beginning June 2020, UNHCR was conducting remote resettlement interviews via video/phone calls for refugees in a secure and confidential manner, and announced that it would communicate with refugees individually to schedule resettlement interviews and final verification.

During this period, UNHCR has not been able to conduct resettlement interviews, stating via its websites that there is currently no indication that resettlement programs will be cancelled; however, there may be a long delay before interviews are conducted with refugees whose file has been submitted to the resettlement country by the authorities of that country. “If you have already been interviewed by the resettlement country, it may take longer than usual to decide on your file”.

It also announced that there is a temporary suspension of all departure arrangements for refugees to travel to countries that have offered their resettlement, and it is not known for how long the departure of resettlement will be postponed.

It then stopped the announcement and warned refugees not to submit any applications or correspondence for resettlement and that only UNHCR’s resettlement unit selects cases.[16]

Thus, refugees became stuck between staying in Egypt without services or support and waiting for resettlement that does not come, especially with a large number of applications submitted to UNHCR. The survey showed that the desire for resettlement is the most requested by more than 70% of the total number of refugees participating in the questionnaire, and none of the participants in the questionnaire wanted to settle in Egypt. This was followed by a preference to travel by passport in the event of non-acceptance of the resettlement request.

Results AndRecommendations

Recommendations to donor countries and humanitarian organizations

- Supporting the continuation of the important role played by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and providing support and assistance to it and the continuation of the functional assistance that enables it to implement urgent relief programs, protection plans and humanitarian assistance.

Recommendations addressed to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- Developing a plan to address the crisis and overcome funding shortfalls

- Demanding funding for aid programs in light of changing international political trends, and actively promoting the needs of refugees and the repercussions of the continuing crisis

- Strengthening services vis-à-vis the number of refugees, establishing a mechanism to ensure that aid reaches those most in need, and adopting a policy of impartiality between nationalities with regard to services

- Intensifying coordination efforts with the government to reach more national cooperation regarding residency, services, detention matters and litigation rights.

- Strengthening communication with refugee communities

Recommendations to Egypt – Host Country

- The need to issue legal legislation that regulates the affairs of refugees in Egypt according to realistic variables and regulates procedures and rights in a way that guarantees their freedom in matters of personal status and freedom of belief and opinion.

- The need to amend the status of refugees in the Egyptian labor law to allow them to obtain a permit to work legally so that they can earn a living and provide for the needs of their families and children.

- The Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) should record and count the real numbers of refugees, including statistics related to age, nationality and gender, as a source for organizations and researchers working in the field of migration to identify more accurately problems, needs and intervention plans.

- Stop linking the prohibition or allowing essential services to the expiration of the validity of the residency, such as the service of communication lines, the issuance of government documents, the request for relief or help, and to limit requirements to the availability of the asylum card.

[1]https://www.facebook.com/RefugeesEgyptAR/photos/a.664632616891863/5864452253576514/

[2]https://www.skynewsarabia.com/middle-east/1566088-%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%86%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%AA%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%B5%D9%8A%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%88%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B7%D9%88%D8%B9%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%84%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AC%D9%8A%D9%94%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A7

https://orient-news.net/ar/news_show/200693

[3]https://egypt.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1021/files/documents/migration-stock-in-egypt-june-2022_v4_arb.pdf

[4]https://1-a1072.azureedge.net/politics/2022/8/11/%D8%AE%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%B7%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AC%D8%A6%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%A8%D9%85%D8%B5%D8%B1-%D9%85%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%B0-%D8%A2%D9%85%D9%86-%D9%88%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%82%D8%A9-%D8%B6%D8%BA%D8%B7

[5]https://www.unhcr.org/eg/wp-content/uploads/sites/36/2022/02/Monthly-statistical-Report_January-2022-_External.pdf

[7]https://help.unhcr.org/egypt/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2022/04/Service-Brochure-Nov-2021-AR-Website.pdf

[8]https://help.unhcr.org/egypt/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2022/10/Service-Brochure-Oct-2022-Ar-Web.pdf

[9]https://www.unhcr.org/eg/ar/what-we-do/main-activities/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B5%D8%AD%D8%A9

[10]https://twitter.com/hrw/status/1595644146991120384?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1595644146991120384%7Ctwgr%5E9825399cd00b94a13d614796e2a7a699d00266ee%7Ctwcon%5Es1_c10&ref_url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bbc.com%2Farabic%2Flive%2F63741295

[11]https://twitter.com/hrw/status/1595644146991120384?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1595644146991120384%7Ctwgr%5E9825399cd00b94a13d614796e2a7a699d00266ee%7Ctwcon%5Es1_c10&ref_url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bbc.com%2Farabic%2Flive%2F63741295

[12]https://www.unhcr.org/eg/ar/what-we-do/main-activities/durable-solutions

[13]https://www.amnesty.org/ar/documents/mde24/4583/2021/ar/

[14]https://www.amnesty.org/ar/location/middle-east-and-north-africa/syria/report-syria/#endnote-4

[15]https://help.unhcr.org/egypt/resettlement/

[16]https://help.unhcr.org/egypt/durable-solution/resettlement/